Saturday, July 31, 2010

July 31

Inside the new GDP numbers. Consumer Metrics Institute, also via CW.

The Aftermath of the Global Housing Bubble Chokes the World Banking System. Michael White (no, not that one).

other fare:

An agnostic manifesto. Ron Rosenbaum, Slate.

Friday, July 30, 2010

Stocks1: What should the return on stocks be?

If, like most investors around today, you started paying attention to the stock market in the 1990s, you might be excused for thinking so.

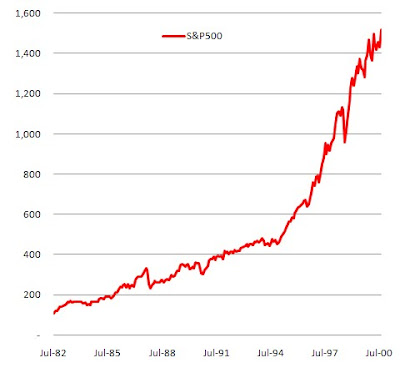

The 18-year equity bull market that started in 1982 and ended in 2000 saw the S&P 500 go parabolic, from about 100 to over 1500, for a cumulative gain in 18 years of a whopping 1317%, or an annualized return of 15.8%.

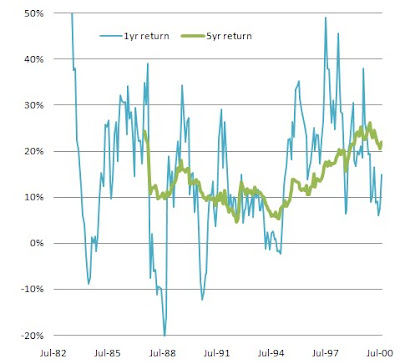

Though there were some dips along the way, most notably in October 1987, the market typically rallied back strongly, so though there was quite a bit of volatility in one-year price returns (based on monthly data, excluding dividends), from a low of -21% to a high of +52%, longer-term returns were always positive, and typically generously so, with five-year returns only falling as low as 5%, but going as high as 26%, and nearly always in double-digit territory.

Though there were some dips along the way, most notably in October 1987, the market typically rallied back strongly, so though there was quite a bit of volatility in one-year price returns (based on monthly data, excluding dividends), from a low of -21% to a high of +52%, longer-term returns were always positive, and typically generously so, with five-year returns only falling as low as 5%, but going as high as 26%, and nearly always in double-digit territory. But does that recent stock price history really tell us much about how stocks should perform? After all, why rely on the memory of the 1990s when in the 2000s we have experienced something entirely different, i.e. two wicked bear markets. From the March 2000 peak of 1550, the market got cut in half to the October 2002 low of 768. It then surged back to a new high in October 2007 of 1576, before again being cut by more than half to a low of 666 in March 2009.

But does that recent stock price history really tell us much about how stocks should perform? After all, why rely on the memory of the 1990s when in the 2000s we have experienced something entirely different, i.e. two wicked bear markets. From the March 2000 peak of 1550, the market got cut in half to the October 2002 low of 768. It then surged back to a new high in October 2007 of 1576, before again being cut by more than half to a low of 666 in March 2009.

One-year returns have therefore ranged from as low as -45% to as high as 50%, and five-year returns from -8% to +13%, but on the whole over that period, the market is down 29%, for an annualized return of -3%.

One-year returns have therefore ranged from as low as -45% to as high as 50%, and five-year returns from -8% to +13%, but on the whole over that period, the market is down 29%, for an annualized return of -3%. Clearly, we're not getting the 10%+ returns we became accustomed to!

Clearly, we're not getting the 10%+ returns we became accustomed to!But, frankly, why should we expect 10% anyways?!

Think of it this way: stock prices should go up commensurate with corporate earnings; and corporate earnings should go up commensurate with the economy. If the economy grew at 5% per year on average, if we were to expect stock prices to go up 10% a year, we must somehow be assuming that corporate profits would be growing on the order of 10% a year also. But how can corporate profits grow 10% a year when the economy is only growing 5% per year?

Suppose corporate profits represented 10% of GDP (about what they do now). And suppose nominal GDP grew 5% a year, and profits grew 10% a year. Then after 10 years, profits would account for 16% of the economy; after 20 years, 25%; after 40 years, 65%; and after 50 years, 100%. Which, needless to say, is patently impossible.

So, what then should we expect?

So, what then should we expect?Well, corporate profits have experienced periods when they grew faster than GDP, but they have also experienced periods when they grew slower than GDP. They have thus regressed to the mean of about 9% of GDP. (Granted, S&P earnings are different than NIPA corporate profits, but for now we'll use them as an imperfect proxy.) (click on any of the charts for a larger image)

So, profits have not consistently grown faster than GDP; they have trended towards the same long-term growth rates.

So, profits have not consistently grown faster than GDP; they have trended towards the same long-term growth rates.And how has GDP grown, historically? To smooth out the volatility, I took a four-year average growth rate of nominal GDP. In periods when inflation was high (the early 1980s), nominal GDP was growing at double-digit rates. But over the long-term, nominal GDP growth has averaged under 6%, and, in fact, in the post WWII-era, has never been lower than it is now.

So, why again have stocks returned double-digits?

So, why again have stocks returned double-digits?

Well, actually, they haven't. In one rare 18-year bull market, they certainly did. But not over the long haul. Adjusted for inflation, low single-digit growth is much more typical, in fact.

So don't go expecting a return to the good ole days of the 1990s. Every time that's happened before (the 1920s, the 1950s and the 1990s), we've ended up with long bear markets to pay for the excesses of the bull markets.

More on valuations in a later post.

July 30

therefore, the fact that Q2 only came in at 2.4% vs the 2.6% expected means we had lower than forecasted growth but off a higher base, right? which should be a good thing, right? not so fast!

the last two quarters of 2009 were both revised downwards by 0.6% each; and 3 of the 4 quarters of 2008 were marked down significantly as well, with revisions of -0.9%, -1.3% and -1.4% in Qs 2, 3 & 4, respectively, while Q1 was unchanged

so, we actually had lower-than-projected growth off a lower base; analysts were forecasting that as of June 30, Real GDP would grow to $13,582.8 billion, up 2.6% from the March 31 level of $13,238.6 billion

what we have instead, though, is that Real GDP is now estimated at $13,216.5 billion, which is 2.7% lower than anticipated

as for the details:

inventories contributed about 45% of the Q2 GDP growth (about 1% of the 2.4%), the 4th straight quarter that inventories boosted GDP --- but the inventory adjustment is likely waning

residential investment contributed 1/4 of the Q2 growth (0.6 of the 2.4%) --- but that was boosted by the tax credit, so it would be surprising if it didn't decline in Q3

PCE grew 1.6% in Q2, down from 1.9% in Q1 --- but on a seasonally-adjusted basis, it declined 0.2%, the first time it has fallen since Q1/2009

final sales to domestic purchasers was up just less than 1%

I know, I'm a glass-half-empty guy; I guess the good news is that net exports had a negative contribution of 2.78, as imports grew faster than exports (4.7% vs. 3.7%), so net exports fell 8%; and seeing as that's the largest negative contribution in years, perhaps it will be revised away, or will be offset in Q3 (how's that for glass half-full?)

government expenditures added to GDP, even at the state and local level --- that may be the last hurrah for state/local spending growth; we'll have to see what happens to overall government spending; Jan Hatzius is expecting a drag:

the overall impact of fiscal policy (combining all levels of government) is likely to go from an average of +1.3 percentage points between early 2009 and early 2010 to -1.7 percentage points in 2011, a swing of about -3 percentage points

the ECRI WLI, by the way, fell a bit further, to -10.7, from -10.5

conversely, a few better-than-expected reports were UofM Confidence (67.8), Chicago PMI (62.3) and NAPM-Milwaukee (66)

on to the links:

Seven faces of "the peril". James Bullard, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review.

executive summary here

Bullard argues that promises to keep the policy rate near zero may be increasing the risk of falling into this state where inflation turns negative and remains there. He argues that promising to remain at zero for a long time is a double-edged sword. This policy is consistent with the idea that inflation and inflation expectations should rise in response to the promise, and that this will eventually lead the economy back toward the targeted equilibrium. But it is also consistent with the idea that inflation and inflation expectations will instead fall, and that the economy will settle in the neighborhood of the unintended steady state, as Japan has in recent years.... The policymaker is completely committed to interest rate adjustment as the main tool of monetary policy, even long after it ceases to make sense.... A better policy response to a negative shock is to expand the quantitative easing program through the purchase of Treasury securities.

Bullard isn't typically as hawkish as Lacker, Hoenig or Plosser; he's more centrist; but he is considered to have more of a hawkish than dovish tilt; in fact, he said so himself:

"I started out saying I was a hawk and I very much see myself in that role. Inflation is very costly for the economy so I’d be very reluctant to let inflation get out of control or do anything that would jeopardize our low and stable inflation rate"

So this is pretty significant that this QE2 argument is coming from a Fed governor with hawkish leanings.

recall that in Bernanke's 2002 speech about making sure deflation doesn't happen here, he recommended that if the Fed funds rate had fallen to zero, the next step would be to lower rates further out the curve, and this could be done in two ways, either by committing to keep the overnight rate at zero for an extended period (which they've done) and/or by "a more direct method, which I [Ben] personally prefer, would be for the Fed to begin announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer-maturity Treasury debt"; he went on to say:

The most striking episode of bond-price pegging occurred during the years before the Federal Reserve-Treasury Accord of 1951. Prior to that agreement, which freed the Fed from its responsibility to fix yields on government debt, the Fed maintained a ceiling of 2-1/2 percent on long-term Treasury bonds for nearly a decade. Moreover, it simultaneously established a ceiling on the twelve-month Treasury certificate of between 7/8 percent to 1-1/4 percent and, during the first half of that period, a rate of 3/8 percent on the 90-day Treasury bill. The Fed was able to achieve these low interest rates despite a level of outstanding government debt (relative to GDP) significantly greater than we have today, as well as inflation rates substantially more variable.

get ready for new lows in yields!

Inflationistas and deflationistas. Paul Krugman.

Should China dump dollars for commodities? What about the "nuclear option" of dumping Treasuries? Can global trade collapse? Michael Shedlock.

Long-term mutual fund flows. ICI.

Equity funds had estimated outflows of $1.32 billion for the week, compared to

estimated outflows of $3.19 billion in the previous week.

that's the 12th sequential week of outflows; just how is the market going up??

oil spill link of the day:

Federal government covering up severity of oil spill? CNN via naked capitalism.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Links, July 29

Reminds me of when the Fed and IMF said in 2006/07 there was no housing bubble in the U.S.

Look at these and judge for yourself:

as Rosenberg said in late 2009:

In answer to the question as to whether prices are in a bubble, all we will say is that when we ran some charts showing Canadian home prices normalized by personal income or by residential rent, what we found is that housing values are anywhere between 15 per cent and 35 per cent above levels we would label as being consistent with the fundamentals. If being 15 per cent to 35 per cent overvalued isn't a bubble, then it's the next closest thing. We are talking about two to three standard deviation events here in terms of the parabolic move in Canadian home prices from their lows. So, if it walks like a duck...

other fare: a survey of some apocalyptic, end of empire, collapse-type thinking --- and its not just Igor Panarin and Gerald Celente thinking such thoughts:

Sun Could Set Suddenly on Superpower as Debt Bites. Niall Ferguson, RealClearWorld.

The year America dissolved. Paul Craig Roberts, Counterpunch.

Why societies collapse. Jared Diamond.

Part I and Part II of interviews of Jim Rickards on King World News on comparison of US to Roman Empire.

The Collapse Of The American Empire And The Rebalancing Of The World.

China or the U.S.: Which Will Be the Last Nation Standing? Richard Heinberg, Post Carbon Institute.

Closing the 'Collapse Gap': the USSR was better prepared for collapse than the US. Dmitry Orlov.

The coming end of the American empire. Chalmers Johnson.

Complexity and Collapse: Empires on the Edge of Chaos. Niall Ferguson, Foreign Affairs.

The Center does Not Hold... But Neither Does the Floor. Jim Kunstler.

American Denial: Living in a Can’t-Do Nation. Tom Engelhardt.

p.s. my mental health is fine; but I find the prospect of such a low-probability-but-very-high-impact event intellectually fascinating --- and naive to dismiss as impossible

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Links, July 28

2nd-half slowdown update. Calculated Risk.

the China story:

China and bust? Ed Harrison via naked capitalism.

Just how risky are China's housing markets? Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu; voxeu.

China Banks Said to See Risks in 23% of $1.1 Trillion Infrastructure Loans. Bloomberg.Our look at the available data strongly suggests that prices are quite risky at current levels, and that it would take little more than a modest decline in expected appreciation to engender sharp drops in prices.... [despite strong income growth in urban China] Price-to-rent ratios have increased by at least 30% over the past 3 or so years in each of these cities.... real, constant quality land values increased by over 750% since 2003 in the Chinese capital... to be very difficult to explain fundamentally... owners must be expecting very high rates of price appreciation for these price-to-rent ratios to be sustainable... this sort of backward looking expectation formation is a classic element of bubble psychology... Reinhart and Rogoff’s recent study of financial crises often finds the genesis in the country’s property markets. Recent data indicate there is reason to suspect a similar predicament in China’s housing sector. Whether it leads to a full blown crisis is another matter, of course, that depends upon the amount of leverage in the system and the safety and soundness of the regulatory environment, among other factors.

Chinese banks may struggle to recoup about 23 percent of the 7.7 trillion yuan ($1.1 trillion) they’ve lent to finance local government infrastructure projects, according to a person with knowledge of data collected by the nation’s regulator....

Only 27 percent of the loans to the financing vehicles can be repaid in full by cash generated by the projects they funded, the person said....

The China Banking Regulatory Commission has told banks to write off non-performing project loans by the end of this year.

Chinese Banks At Risk, Part 1. Patrick Chovanec, An American Perspective from China.

Ratings Understate `Dangerous' Chinese Local Government Risks, Dagong Says. Bloomberg.

The PBoC can't easily raise interest rates. Michael Pettis, China Financial Markets.

re the above stories about the Chinese banking system:

I would suggest, based on my pretty extensive experience in emerging markets, that we should assume the real problem is worse than the initial evaluation. It almost always is....

I agree that these loans won’t pose a risk to the banking system, but that doesn’t mean that there won’t be huge losses. It just means that the losses will be covered by the household sector. For years I have been arguing that without liberalizing interest rates and pushing through governance reform, there won’t be meaningful reform in the domestic financial system. It isn’t even conceivable to me that a combination of rapid credit growth, socialized credit risk, severely repressed interest rates, and serious lack of transparency could ever have led to anything other than large-scale capital misallocation and rising debts.

So of course there are problems in the banking system, and of course there is a lot of debt piling up in all sorts of unexpected places, and of course bit-by-bit we will get more information, like this leaked CBRC report....

One of the problems with a severely repressed financial system, especially one with rapid credit expansion, is that there tends to be a huge amount of capital misallocation supported by borrowing, and in an increasing number of cases it is only the artificially-reduced borrowing costs that allow these investments to remain viable. I worry that even if the PBoC wanted to raise rates, it would not be able to do so without exposing how dependent borrowers are on artificially cheap capital....

of course it is not just the PBoC that has this addiction to repressed interest rates. Many years of very low cost borrowing has created a huge dependency on low interest rates among SOEs, local governments, and other creditors of the bond markets and the banks (not to mention the banks themselves), all of whom are directly or indirectly funded by long-suffering households....

All this might sound like I am effectively recommending that the PBoC continue to repress interest rates, but of course repressed interest rates are what caused the problem in the first place. To continue to do so simply makes the underlying problem worse, by piling on even more non-viable debt. Rather than suggest that the PBoC must keep rates low, what I am really arguing, I guess, is that this is a very difficult trap from which to escape.

What can the authorities do? If Beijing raises interest rates quickly, debt and bankruptcy will surge and growth will collapse – although the eventual rebalancing of the economy might happen much more quickly.

If they don’t raise interest rates, they can keep growth high for a while longer, but the amount of reserves and misallocated capital will continue rising, making the eventual cost of raising interest rates even higher. The risk is a Japanese-style stalemate in which for many years the authorities are forced to keep rates too low because they simply cannot countenance the alternative, and during this time consumption growth continues to struggle.

Finally, if they raise interest rates slowly, they will slow growth while still suffering many more years of worsening imbalances, until rates are finally high enough to begin reversing the imbalances. But for this strategy to work, they would need a very, very accommodative external sector – China’s domestic imbalances require high trade surpluses until they are finally reversed.

So there’s the dilemma: they’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t.

Now let us stress-test the central banks. Terrence Keeley, FT.

Consider Asian central banks, with their total of $5,000bn in foreign reserves. These assets are often mistakenly seen as a sign of strength. As the vast bulk of liabilities against these reserves are denominated in local currencies, a prolonged period of US dollar and/or euro weakness would generate unprecedented marked-to-market losses. A 20 per cent appreciation of the renmimbi versus the People’s Bank of China’s owned foreign assets would thus result in a hit to Chinese federal finances of some 10 per cent of domestic GDP

oil spill link of the day:

Of Course Clean Up Workers Can't Find the Oil ... BP Used Dispersants to Temporarily Hide It, So Now It Will Plague the Gulf For Years. Washington's Blog.other fare:

Slowed food revolution. Heather Rogers, The American Prospect.

Who killed the climate bill. Foreign Policy.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Links, July 27

if you haven't registered at GMO and can't view the report at that link, it can be seen (though not downloaded nor printed) also at scribd

If the examples of history are ignored (as is all too often the case) then policy error is likely to be a serious source of deflationary pressure. This is the last thing a debtladen economy needs, especially a debt-laden economy that is teetering on the brink of deflation anyway. But that doesn’t mean that policy makers won’t try to tighten. Indeed, one of the world’s worst economists and a paragon of orthodox belief, Alan Greenspan, opined in a recent Wall Street Journal OpEd that “an urgency to rein in budget deficits” is “none too soon.” Did you need more evidence that this was a really bad idea!?!

And Montier's old pal, Albert Edwards (still at SocGen) also has some stuff to say:

For Edwards, the Japanese lesson still holds…. FT Alphaville.

Ten Stock-Market Myths That Just Won't Die. Brett Arends, WSJ.

The consumption gap. Stephen Roach, Foreign Policy.

oil spill link of the day:

Conservatism's Death Gusher. George Lakoff, Berkely Blog.

Monday, July 26, 2010

Links, July 26

more on money supply and velocity, from a historical perspective:take the regular equation of exchange, MV=PY (where M = money supply, V=velocity, and PY = nominal GDP or aggregate demand) and expand the money supply term, M, such that M=Bm where B = monetary base and m = money multiplier. This expanded version of the equation of exchange can be stated as follows:

BmV = PY

In this form, the equation says (1) the monetary base times (2) the money multiplier times (3) velocity equals (4) nominal GDP or total spending (i.e. aggregate demand). The Fed has complete control over the monetary base, B. It has less control over the money multiplier,m, but still can shape it to some degree as it is currently doing by paying banks interest payments to sit on excess reserves. (Imagine what might happen to m if the Fed started charging a penalty for holding excess reserves? We saw how excited the stock market got just at the idea of dropping interest paid on excess reserves.) The Fed can also influence V by setting an explicit nominal target (e.g. inflation, price level or nominal GDP target--the latter being my first choice). In short, the Fed has enough influence that if it really wanted to it could do much to stabilize BmV (or MV). And all of this could happen without resorting to more fiscal

policy.

The Death of Paper Money. Ambrose-Evans Pritchard, Telegraph.

Betting on a bubble, bracing for a fall. John Hussman.

The financial markets are in a bit of a fight here between technicals and fundamentals... suggesting that investors are eager to re-establish a speculative tone to the market. At the same time, fundamentals are bearing down hard on the market. We continue to observe a clear deterioration in leading indicators of economic activity.

Over the short-term, my impression is that the technicals may hold sway for a bit. The economic data points simply do not come out every day, and to the extent that economic news is not perfectly uniform in its implications, the eagerness of investors to speculate can easily dominate briefly.

....

We certainly know of many valuation indicators that suggest that stocks are "cheap" here. Unfortunately, they don't demonstrate any reliability in historical tests. It is almost mind-numbing to observe how many analysts confidently make valuation claims about the market on CNBC, evidently without ever having done any historical research. If you don't require evidence, you can say anything you want.

....

The government has issued trillions of dollars in new debt in the attempt to sustain the previous misallocation of capital - trying to prevent bad loans from failing; to keep elevated home prices from adjusting to normal levels relative to income; to maintain unsustainable consumption habits; and to subsidize purchases of autos, homes and other big-ticket items that have weak intrinsic demand because people already have too much debt. Huge chunks of national savings that should have been available for productive economic activity have been diverted in an effort to maintain an inefficient status quo.

We now have corporations sitting on a mountain of what seems to be "cash." But in fact, they are not holding cash. They are holding a pile of government debt that was issued during this crisis, which somebody has to hold until the debt is retired. Corporations just happen to be "it" in this game of hot potato. Bernanke and Geithner have done nothing but incur public losses in order to defend private interests. This is not skilled leadership - it is misappropriation.

Moreover, we've failed to address the underlying problems - the need to ultimately restructure debt obligations so that they are in line with the cash flows available to pay them; the need for prices and production to shift in a way that reflects a different mix of consumption, investment and financial activity. The markets appear to be crossing their fingers that this won't happen - that the combination of opaque disclosure and massive fiscal deficits will simply make the problem go away; that a big enough "stimulus" package will "jump-start" consumers to their previous habits. The historical evidence on this is not encouraging. In the meantime, we've created yet another mountain of debt. Given the fresh deterioration our Recession Warning Composite and other leading measures of economic activity, our economic challenges seem likely to persist much longer than they should have.

Friday, July 23, 2010

Links, July 23

Leading indicators.... more Fed please! EconompicData.

Loblaw seeing price deflation. CBC.

The Mean of the New Normal Is an Observation Rarely Realized: Focus Also on the Tails. Richard Clarida, PIMCO.

Beware those black swans. Nassim Nicholas Taleb in the New Statesman.

BP link of the day:

Big storm to hit Gulf of Mexico... all oil relief oerations will be suspended.... cap will stay on, unattended. Washington's Blog.

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Links, July 21

Paul Krugman quotes Goldman Sachs in his post Why I worry.

By our estimates, (federal) fiscal policy has contributed +2½ percentage points (annualized) to real GDP growth from early 2009 to mid-2010. From mid-2010 to mid-2011, we estimate an impact of about -¼ percentage point—i.e. 2¾ percentage points less than before—even under our baseline assumptions of extended unemployment benefits, more aid to state governments, and at least a temporary extension of the bulk of the 2001-2003 tax cuts. We need a lot of improvement in private sector activity to offset this swing, and at the moment it unfortunately doesn’t look like we’re getting it.Existing Homes: Months of Supply and House Prices. Calculated Risk.

(conservatively) projects months of supply to rise from 8.3 in May to 10.4 in July

Meanwhile, in the Chinese property market. Joseph Cotterill, FT Alphaville.

refers to an NBER working paper, which includes this doozy:

Much of the increase in prices is occurring in land values. Using data from the local land auction market in Beijing, we are able to produce a constant quality land price index for that city. Real, constant quality land values have increased by nearly 800% since the first quarter of 2003, with half that rise occurring over the past two years.discussed further at Econbrowser.

Also by Mish in Ponzi "shark loans" fuel China's housing bubble; home sales plunge 44% in Xiamen; bubble busts in Tianjin.

The expected inflation curve. David Beckworth.China's property bubble is now on the verge of collapse. Transaction volumes are significantly down and declining volume is how property bubbles always burst. In simple terms, the pool of greater fools eventually runs out....

A typical Beijing flat costs about 22 times average incomes in the city, state media said Monday, highlighting the challenge China faces providing affordable housing amid a property boom.A 90-square-metre (968-square-foot) apartment in Beijing cost 1.6 million yuan (236,000 dollars) last year, the China Daily said, citing an independent report.That compared to an average household disposable income of around 71,000 yuan in 2009, according to city figures.

shows inflation expectations continuing downward path

Paralyzed by debt. Roger Lowenstein. NYT.

Which raises the issue: how much of that debt will have to be repaid before people return to their customary, and stimulative, profligacy? ... To return to the status quo of before the housing boom — say, back to debt to income ratios prevailing in 2000 — it would take five more years of deleveraging at the current rate.

other fare:

Ego: Illusionist, Trader's Nemesis. Kent Thune, via The Big Picture.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Links, July 20

Reflections on the sovereign debt crisis. Edward Chancellor, GMO.

Credit crunch 2010? Michael Snyder, Daily Markets.

Gary Shilling on Bloomberg. via YouTube.Over the past several decades, one of the primary engines of U.S. economic prosperity has been a constantly expanding debt spiral. As long as the U.S. government, state governments, businesses and American consumers could all continue to borrow increasingly large amounts of money, the economy was going to continue to grow and “the greatest party on earth” could continue. But many of us knew that if anything ever came along and significantly interrupted that debt spiral, it could cause a credit crunch even more severe than we saw at the beginning of the Great Depression back in the 1930s....

once a deflationary cycle starts, it tends to feed on itself....

Now that governments around the world are pulling back and are beginning to implement austerity measures, the “sugar rush” of the stimulus money is wearing off and the original economic decline is resuming. All that the trillions in “stimulus” did was to give the world economy a temporary boost and get us into a whole lot more debt.....

the United States is in the early stages of a truly historic financial implosion

- calls for Euro parity (its up now, but we're in calm btw 2 storms)

- likes US long bond to get to 3% and 10-year to 2%

- due to a decade of very low growth, deleveraging and deflation

Q&A With David Rosenberg: The Bearish Outlook. WSJ via ZeroHedge.

it would seem reasonable to expect that the equity market will trade down to a valuation level that is historically commensurate with the end of secular bear markets. This would typically mean no higher than a price-earnings multiple of 10x and at least a 5% dividend yield on the S&P 500. So, we very likely have quite a long way to go on the downside....

when the equity market was hitting its recovery highs in early spring, it reflected a widespread view that the green shoots of 2009 would be extended into a sustainable growth phase into the future. Not a good assumption then; and not one now....

the recovery has really been one part bailout stimulus, to one part fiscal stimulus, to one part monetary stimulus, to one part inventory renewal....

This is what keeps me up at night — kicking the can down the road in terms of addressing the global debt problem will only end up making the situation worse. Governments seem to believe that the solution to a debt deleveraging cycle is to create even more debt. But delaying the inevitable process of mean-reverting debt and debt-service ratios back to historical norms will be even more painful....

with the median age of the boomer population turning 55 in the U.S., there is a very strong demographic demand for income and with bonds comprising just 6% of the household asset mix, this appetite for yield will very likely expand even further in coming years

along those lines...

The answer is the domestic private sector. Rebecca Wilder, News N Economics.

Alex, the question is "who will buy all the debt?"

an almost apocalyptic but interesting take on history of fiscal finance:

Welfare and Warfare. The Burning Platform.

The United States has hit the proverbial jackpot, with a rapidly aging population, a $106 trillion unfunded liability, an administration that has piled more unfunded healthcare obligations upon our future unborn generations, spineless politicians that refuse to address the crisis, and as icing on the cake 700 military basis spread throughout the world and an annual defense budget of $895 billion....

The United States of America is the modern day Roman Empire. Any reasonably intelligent person with a calculator can figure out that this will end in economic collapse. And still, we do nothing. Not only do we do nothing, we push our foot down on the accelerator by spending $2 trillion on wars of choice, commit $16 trillion to new drug coverage for seniors, and national healthcare for all at an unknown cost. There is one law that cannot be skirted. An unsustainable trend will not be sustained....

[a trend] took root in the United States in the early 1980s. Citizens became consumers. The only way for a country to achieve long-term growth is for its citizens to save more than they spend. These savings can then be invested within the country to insure that prosperity could continue for future generations. A country of only consumers will eventually collapse under the weight of debt and lack of investment

Monday, July 19, 2010

Links, July 19

"The issue which has swept down the centuries and which will have to be fought sooner or later is the People versus the Banks."

Lord Acton (the same man who said "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely")

The US banking recovery is a sham. David Stevenson, MoneyWeek.

JPMorgan's recent quarterly profits... have now climbed right back to 2007's high point. That's nothing short of amazing. And it's more than enough to get bank bulls quite excited again.also comments on FASB 157, which allows banks to book profits due to the deterioration in its bonds' prices --- i.e. the company still owes the face value of its outstanding debt, but it can pretend it owes less because its bonds' market values have fallen, and this, apparently, constitutes "profits"

But hang on a minute. Maybe there's a con trick being played here.

For one thing, JP Morgan hasn't achieved any 'real' growth. The bank's revenues actually fell by 8%. Investment banking and fixed-income trading results both dropped.

So where did all the money come from?

Well, the bank only turned in such a 'good' result because it slashed its "provision for credit losses" by two thirds, from $9.7bn to $3.4bn. In other words, all (and more) of JP Morgan's latest profit was due to the bank making a much lower allowance for bad debts – loans that could go sour because the debtors can't repay to the bank the money they've borrowed.

A generation of overoptimistic equity analysts. McKinsey Quarterly.

equity analysts have been overoptimistic for the past quarter century: on average, their earnings-growth estimates—ranging from 10 to 12 percent annually, compared with actual growth of 6 percent—were almost 100 percent too highDon't take the bait. John Hussman.

Important metrics of economic activity are slowing rapidly. Notably, the ECRI weekly leading index slipped last week to a growth rate of -9.8%. While the index itself was reported as unchanged, this was because of a downward revision to the prior week's reading to 120.6 from the originally reported 121.5. The previous week's WLI growth rate was revised to -9.1% from the originally reported -8.3% rate. Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Fed Survey dropped to 5.1 from 8.0 in June, while the Empire State Manufacturing Index slipped to 5.1 from 20.1. The Conference Board reported that spending plans for autos, homes, and major appliances within the next six months all dropped sharply. These figures are now at or below the worst levels of the recent economic downturn, and are two standard deviations below their respective norms - something you don't observe during economic expansions....comments from David Rosenberg:

The U.S. economy continues to face the predictable effects of credit obligations that quite simply exceed the cash flows available to service them, coupled with the predictable shift away from the consumption patterns that produced these obligations....

Investors who allow Wall Street to convince them that stocks are generationally cheap at current levels are like trout - biting down on the enticing but illusory bait of operating earnings, unaware of the hook buried inside.

I continue to urge investors to have wide skepticism for valuation metrics built on forward operating earnings and other measures that implicitly require U.S. profit margins to sustain levels about 50% above their historical norms indefinitely. Forward operating earnings are Wall Street's estimates of next year's earnings, omitting a whole range of actual charges such as loan losses, bad investments, restructuring charges, and the like. The ratio of forward operating earnings to S&P 500 revenues is now higher than it has ever been. Based on historical data, the profit margin assumptions built into forward operating earnings are well beyond two standard deviations above the long-run norm. This is largely because... forward operating earnings are heavily determined by extrapolating the most recent year-over-year growth rate for earnings. In the current instance, this is likely to overshoot reality, and in any event, has little to do with the long-term cash flows that investors can actually expect to receive over time.

GMO Quarterly Letter. Jeremy Grantham.The growth rate on the ECRI leading index did it again! It sank further into negative terrain, now at -9.8% during the week ending July 9, down from -9.1% the prior week. This was the tenth deterioration in a row and the growth index is now negative for six straight weeks. We have never failed to have a recession with the ECRI at current levels but there is also inherent volatility in the index that requires acknowledgment. Our reckoning is that in the past few weeks, the index has gone from pricing in even-odds of a double-dip to two-in-three odds. It may take a while, but Mr. Market will figure it out before long.

All we hear from in the mainstream economics community is that double-dip recessions are out of the question because they are “extremely rare” events. The double-dip deniers say that this only happened in 1982 because of the renewed sharp tightening by the Fed (as if we aren’t going to see a sharp fiscal withdrawal this time around to take its place). What is it that these economists and strategists don’t see?

These “extremely rare” events have been the norm for the past 24 months: negative nominal GDP growth; negative operating earnings; a massive contraction in credit; a 30% slide in home prices (these same economists — Bernanke too — were telling everyone that home prices never deflate over a 12-month time span ... but they did this time!); a record-high duration of unemployment.

The past 24 months have given us a lifetime of “extremely rare” events...

Relying on indicators that have been useful in previous post-WW2 recessions is like comparing the statistics of U.S. football teams versus the statistics of Australian football teams. They may be called the same thing but they are different sports. The economy is one sick puppy and we are seeing first hand now what it looks like once the crutch of government support is taken away.

Hoisington Quarterly Review and Outlook. Van Hoisington and Lacy Hunt.

Stress-testing Europe's banks won't stave off a deflationary vortex. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Telegraph.

Euroland's authorities are inflicting a triple shock of fiscal, monetary, and currency tightening on a broken economy. They are doing so in a region where industrial output is still 14pc below its peak, where growth barely scraped above zero over the winter "recovery", and where youth unemployment is at 40pc in Spain, 35pc in Slovakia, 29pc in Italy, and 26pc in Ireland.

They seem unaware that China is slowing and the US is tipping into a second leg of the Long Slump. Last week's collapse in America's ECRI leading indicator to -9.8 marks the end of the V-shaped rebound. If this means what it normally means - recession within three months - Europe must take immediate action to prevent being drawn into a deflationary vortex. Spiralling public debt precludes further Keynesian spending, so this must come from central bank stimulus. Tight fiscal policy offset by ultra-loose money is the only option for Europe, the US, and Japan....

The US Conference Board's indicator is not yet flashing a red alert, but that is because it gives weight to "yield curve inversion", where long rates fall below short rates. This indicator is meaningless in a Japan-style bust where policy rates are zero.

BP link of the day:

What if he's right? James Howard Kunstler, Clusterfuck Nation.

Matt Simmons has been around the oil business for forty years. His knowledge is deep and comprehensive. From the beginning of the BP Macondo blowout incident in April, he's taken the far out position that the well-bore is fatally compromised and that BP has been consistently lying about their operations to stop the flow of oil. Perhaps most radically, Simmons claims that an oil "gusher" is pouring into the Gulf some distance from the drilling site itself....

Simmons's current warning about the situation focuses on the gigantic "lake" of crude oil that is pooling under great pressure 4000 to 5000 feet down in the "basement" of the Gulf's waters. More particularly, he is concerned that a tropical storm will bring this oil up - as tropical storms and hurricanes usually do with deeper cold water - and with it clouds of methane gas that will move toward the Gulf shore and kill a lot of people.

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Links, July 18

Implications of a likely economic downturn and Misallocating resources.

the latter includes this gem:

There is little question that we have, for more than a decade, squandered our productive resources in the pursuit of bubbles. Almost unbelievably, real private gross domestic investment is lower today than it was 12 years ago, and much of the gross domestic investment that we have made in the interim has been destroyed in mispriced speculative activity such as residential construction and commercial real estate development.while the former includes this:

If our only response to excess consumption is to pull out all the stops trying to "stimulate" consumption every time it falters; if our only response to reckless lending is to defend the bondholders every time their poor allocation of capital threatens to produce a loss for them, then quite simply, we will destroy our economy, our future, and our standard of living. The last thing I want to be is a cheerleader for the bears here. But quite honestly, it's difficult to envision a return to long-term saving, productive investment, and thoughtful allocation of capital until - as happens every two or three decades - the speculative elements of Wall Street are crushed to powder.

Over the short and intermediate-term, credit crises are invariably deflationary, because they prompt a frantic demand for default-free government paper, which raises its value relative to goods and services (another phrase for deflation). So despite the huge increase in government obligations during these periods, you generally don't see inflationary pressures in the early years because that supply is eagerly absorbed. Short-term interest rates are pressed near zero, and monetary velocity tends to collapse. Commodities are usually hard hit as well, so investors who are concerned about inflation risk or are chasing gold here may have the long-term story right, but they probably have it too early to weather the interim volatility comfortably.as well as this:

Over the long-term, massive increases in government liabilities do have inflationary impact. This imposes a real burden, not simply a paper one. If the holder of government currency can command a certain stock of real goods and services, and then the government debases that currency so that it can command a lesser stock of real output, then it is undeniable that the difference in real value has been implicitly

transferred to the government to finance its spending. While I do expect that TIPS, commodity exposure and precious metals will be important inflation hedges in the years ahead, investors chasing these assets here may have a difficult road. It is best to accumulate such assets when they are in liquidation, not when they are being chased on the basis of overly simplistic theories of inflation.

Meanwhile, I continue to believe that both Bernanke and Geithner's hands should be tied quickly. If we have learned anything over the past 18 months, it is clear that these bureaucrats can misallocate an enormous quantity of public resources with mind-numbing speed. The diversion of public resources to the bondholders of failing financials - to precisely the worst stewards of capital in society - is not stimulative, but ruthless. A second economic downturn should encourage the repudiation of the policies that Bernanke and Geithner pursued during the first.Musings on China and Japan. Vitaliy Katsenelson via ZeroHedge.

By all appearances, Ben Bernanke has a four-second tape in his head that says "We let the banks fail during the Depression, and look what happened." Then the tape repeats. There is no subtlety that says, "yes, but we let the banks fail in the most disruptive and disorganized way possible, forcing them into piecemeal liquidation as Lehman had to do. Today, the FDIC is fully capable of preserving and transferring the operating entity while properly cutting away the failing bondholder and stockholder liabilities so that depositors and customers are not affected." This understanding would prove useful in the event we observe further credit strains.

Basic ethical principle dictates that policy makers should not burden ordinary Americans to pay the losses that well-informed bondholders voluntarily took when they lent money to failing institutions

significantly excerpted:

China is not a black swan, because a black swan is a rare, significant, and unpredictable event. However, the consequences of what is transpiring in China and Japan are for the most part predictable (especially if I am writing about it). We don't know when they will play out, but they are predictable.

Nassim Taleb, one of my favorite thinkers, who brought the black Swan to life in his books Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan,... solved my dilemma with China by creating a new swan: "grey"– a rare, significant, but predictable event (though the timing is still unknown, or perfectly known only with the benefit of hindsight.)...

What really amazes me is how people who would not trust the US or European governments to do their laundry, have unconditional faith in Chinese government involvement in its very complex economy.

The Chinese government brainwashes its people the same way the Russians and Soviets brainwashed theirs: by controlling and censuring media... However, I am amazed that the Chinese government has been able to brainwash people who reside outside of China.

No, an economy in large part controlled by the state is not superior to ours. Greater control over their economy allows the Chinese government to pull the economy out of recession a lot faster than in the democratic countries, but there is no free lunch. Their actions will just lead to greater excesses and imbalances down the road.

It seems that as Westerners we have an inferiority complex when it comes to Asian cultures. Chinese uniqueness is praised today the same way Japanese superiority was in the 1980s. I even remember reading Russian newspapers in Russia, in 1989, praising the Japanese work ethic and their unique culture and spouting predictions of the continuance of Japanese dominance. I can only imagine how the mainstream press in the US was caressing Japanese uniqueness in the late ’80s, especially as the

Japanese were invading (buying) Times Square and the State of California.

What is very interesting about it is that today all those Japanese cultural advantages are looked upon as disadvantages. For instance, “saving face” did not allow Japan to deal sufficiently with failed companies; their economy was full of semi-dead, zombie companies, which did not allow the healthy ones to prosper. Their employment-for-life system that was praised to the heavens during the Japanese golden age is now killing productivity of the economy....

Back to China. Even if the Chinese are harder-working and more entrepreneurial than Americans and Europeans, that doesn't mean the laws of economics are somehow suspended in China – they are not. The Chinese economy was geared for high global growth, while now much lower growth is in the cards. The excesses created by 14% of GDP being “stimulated” into the economy through a fire hose have led to significant overcapacity. It will take time for these excesses to be dealt with, even in a country full of super-hard-working people...

Government is not and never will be an efficient allocator of capital. It empowers bureaucrats, which in turn leads to corruption, which further misallocates capital. The size of the bribe or strength of the personal relationship decides the flows of capital instead of the invisible hand that funnels capital from low to high uses.

I keep thinking about the possible consequences of the Chinese overcapacity bubble pop. It is relatively easy to understand what will happen in Japan: deflation will quickly turn into hyperinflation as government is forced to print money to service its debt and social obligations. They'll announce and may even execute austerity measures, but those will be a decade or two too late. The Japanese yen will likely decline, though maybe not right away, as Japan owns a lot of US dollars and may be forced to sell them.

The Chinese situation is far more complex. China has tremendous overcapacity, but overcapacity is deflationary. It will drive prices for commodities down, and prices of Chinese-made goods will likely decline as well. Demand for industrial goods will collapse, pushing their prices down. But China will also have to deal with a lot of bad debt and will likely have to print money to do so – which is inflationary.

The popping of both the Chinese and Japanese bubble economies will lead to higher US, and likely global, interest rates.

I don't normally post full articles, just links with excerpts, but the following two commentaries moved me to post them in full:

Obama is barely treading water. Mort Zuckerman, US News.

The hope that fired up the election of Barack Obama has flickered out, leaving a national mood of despair and disappointment. Americans are dispirited over how wrong things are and uncertain they can be made right again. Hope may have been a quick breakfast, but it has proved a poor supper. A year and a half ago Obama was walking on water. Today he is barely treading water. Then, his soaring rhetoric enraptured the nation. Today, his speeches cannot lift him past a 45 percent approval rating.

There is a widespread feeling that the government doesn't work, that it is incapable of solving America's problems. Americans are fed up with Washington, fed up with Wall Street, fed up with the necessary but ill-conceived stimulus program, fed up with the misdirected healthcare program, and with pretty much everything else. They are outraged and feel that the system is not a level playing field, but is tilted against them. The millions of unemployed feel abandoned by the president, by the Democratic Congress, and by the Republicans.

The American people wanted change, and who could blame them? But now there is no change they can believe in. Sixty-two percent believe we are headed in the wrong direction—a record during this administration. All the polls indicate that anti-Washington, anti-incumbent sentiment is greater than it has been in many years. For the first time, Obama's disapproval rating has topped his approval rating. In a recent CBS News poll, there is a meager 15 percent approval rating for Congress. In all polls, voters who call themselves independents have swung against the administration and against incumbents.

Even some in Obama's base have turned, with 17 percent of Democrats disapproving of his job performance. Even more telling is the excitement gap. Only 44 percent of those who voted for him express high interest in this year's elections. That's a 38-point drop from 2008. By contrast, 71 percent of those who voted Republican last time express high interest in the midterm elections, above the level at this stage in 2008. And these are the people who vote.

Republicans are benefiting not because they have a credible or popular program—they don't—but because they are not Democrats. In a recent Wall Street Journal / NBC poll, nearly two thirds of those who favor Republican control of Congress say they are motivated primarily by opposition to Obama and Democratic policy. Disapproval of Congress is so widespread, a recent Gallup poll suggests, that by a margin of almost two to one, Americans would rather vote for a candidate with no experience than for an incumbent. Throw the bums out is the mood. How could this have happened so quickly?

The fundamental problem is starkly simple: jobs and the deepening fear among the public that the American dream is vanishing before their eyes. The economy's erratic improvement has helped Wall Street but has brought little support to Main Street. Some 6.8 million people have been unemployed in the last year for six months or longer. Their valuable skills are at risk, affecting their economic productivity for years to come. Add to this despairing army the large number of those only partially employed and those who have given up their search for work, and we have cumulative totals in the tens of millions.

Many people who joined the middle class, especially those who joined in the last few years, have now fallen back. It's not over yet. Millions cannot make minimum payments on their credit cards, or are in default or foreclosure on their mortgages, or are on food stamps. Well over 100,000 people file for bankruptcy every month. Some 3 million homeowners are estimated to face foreclosure this year, on top of 2.8 million last year. Millions of homes are located next to or near a foreclosed home, and it is the latter that may determine the price of all the homes on the street. There have been dramatically sharp declines in home equity, representing cumulative losses in the trillions of dollars in what has long been the largest asset on the average American family's balance sheet. Most of those who lost their homes are hard-working, middle-class Americans who had lost their jobs. Now many have to use credit cards to pay for essentials and make ends meet, and they are running out of credit. Another $5 trillion has been lost from pensions and savings.

But it is jobs that have long represented the stairway to upward mobility in America. For a long time, it was feared they were vulnerable to offshore competition (and indeed still are), but now the erosion is from economic decline at home. What happens as those domestic opportunities recede? Middle-class families fear they have become downwardly mobile and have not hit the bottom yet. The financial security that was once based on home equity and a pension has been swept away.

In a survey just released, the Pew Research Center explored the recession's impact on households and how they are changing their spending and saving behavior. Nearly half the adults polled intend to boost their savings, cut their discretionary budgets, and cut their debt loads. The report concludes that the present enforced frugality will outlast the recession and its overhang. Fully 60 percent of those ages 50 to 61 say they may delay retirement. What does that mean for the young would-be employees entering the labor force over the next few years?

The administration's stimulus program, because of the way Congress put it together, has created far fewer jobs than anyone expected given the huge price tag of almost $800 billion. It was supposed to constrain unemployment at 8 percent, but the recession took the rate way above that and in the process humbled the Obama presidency. Some 25 million jobless or underemployed people now wish to work full time, but few companies are ready to hire. No speech is going to change that.

Little wonder there has been a gradual public disillusionment. Little wonder people have come alive to the issue of excess spending with entitlements out of control as far as the eye can see. The hope was that Obama would focus on the economy and jobs. That was the number one issue for the public—not healthcare. Yet the president spent almost a year on a healthcare bill. Eighty-five percent in one poll thought the great healthcare crisis was about cost. It was and is, but the president's bill was about extending coverage. It did nothing about the first concern and focused mostly on the second. Even worse, to win its approval he accepted the kind of scratch-my-back deal-making that suggests corruption in the political process. And as a result, Obama's promise to change "politics as usual" disappeared.

The president failed to communicate the value of what he wants to communicate. To a significant number of Americans, what came across was a new president trying to do too much in a hurry and, at the same time, radically change the equation of American life in favor of too much government. This feeling is intensified by Obama's emotional distance from the public. He conveys a coolness and detachment that limits the number of people who feel connected to him.

Americans today strongly support a pro-growth economic agenda that includes fiscal discipline, limited government, and deficit reduction. They fear the country is coming apart, while the novelty of Obama has worn off, along with the power of his position as the non-Bush. His decline in popularity has emboldened the opposition to try to block him at every turn.

Historically, presidents with approval ratings below 50 percent—Obama is at 45—lose an average of 41 House seats in midterm elections. This year, that would return the House of Representatives to Republican control. The Democrats will suffer disproportionately from a climate in which so many Americans are either dissatisfied or angry with the government, for Democrats are in the large majority in both houses and have to defend many more districts than Republicans. In any election year, voters' feelings typically settle in by June. But now they are being further hardened by the loose regulation that preceded the poisonous oil spill—and the tardy government response.

The promise of economic health that might salvage industries and jobs, and provide a safety net, has proved illusory. The support for cutting spending and cutting the deficit reflects in part the fact that the American public feels the Obama-Congress spending program has not worked. As for the healthcare reform bill, the most recent Rasmussen survey indicates that 52 percent of the electorate supports repeal of the measure—42 percent of them strongly.

It is clear that the magical moment of Obama's campaign conveyed a spell that is now broken in the context of the growing public disillusionment. Obama's rise has been spectacular, but so too has been his fall.

The dangers of a failed presidency. Michael Krieger, via ZeroHedge.

I have been calling Barrack Obama’s Presidency a failure for at least six months now and it seems that I now have considerable company in this assessment as it becomes obvious to most. It is not a failure because of the Republicans. It is not a failure because of events beyond his control. It is a failure because this was a man that filled a depressed and downtrodden nation with the audacity of hope. When I voted for the man I knew it was against my personal financial interests. It was clear what he would do with taxes. Nevertheless, I got to the polls and voted for this fifth avenue creation thinking maybe, just maybe he might do some of the things he said. Most important to me were two issues related to the military-industrial complex (see Eisenhower’s warning on this during his Farewell Address http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8y06NSBBRtY) and civil liberties. George W Bush was turning America into a depressed police state with perpetual war and consolidation of power between a corporate oligarchy and entrenched political class. A nation where the masses voluntarily gave up many of the liberties the founding fathers fought for merely to ease the fear that consumed them and which was propagated by the administration and the media. I and many others that voted for him even though they disagreed strongly with his economic policies thought he would at least reverse this trend. Why did we think this? Cause he said so. How foolish we were.

That being said, the real answer was certainly not John McCain as I think we would be in just as bad shape with him. I think that what this experience has taught us is that the President of the United States answers to others behind the scene. There are many theories on who these others are but I will keep it very simple. There is clearly a power elite that consists of a union between big corporate and financial oligarchs and career bureaucrats in Washington D.C. These are the folks that pull the strings of all administrations. All you have to do is look at the trends that have been in place since George W Bush and continue under Obama to see what these players want. Bigger government and thus more Federal power, more wealth for the oligarchs (thank you Federal Reserve) and an erosion of the middle class, and reduction of civil liberties in the name of the 1984-like never-ending “war on terror.” I believe in a war on terror of my own. A war against the terror that Washington D.C. is constantly trying to inject into your head so that you sheepishly give away all you rights and power to them. That’s my war on terror.

Ok, so what do I mean by “The Dangers of a Failed Presidency.” I mean that it is July of an election year and Obama’s magic spell that held sway over the American people and the world for about three months has completely washed away. I mean that the printed money mirage recovery that we have had to tragically watch is ending and we have no job growth to speak of other than a few hundred thousand census workers. The public has no appetite for more spending and Bernanke has no cover to print more money (yet). As such, if people think things are in freefall now for this administration just wait and see how the next several months pan out. This then brings me to the following quote:

The bottom line here is that Americans don’t believe in President Obama’s leadership,” says Rob Shapiro, another former Clinton official and a supporter of Mr Obama. “He has to find some way between now and November of demonstrating that he is a leader who can command confidence and, short of a 9/11 event or an Oklahoma City bombing, I can’t think of how he could do that.”

I found this quote in an FT article earlier in the week and it sent chills all over my body. This is how the strategists in Washington D.C. think. They are sick, twisted people. This guy doesn’t even realize how sick and twisted what he said is which is why he said it. Imagine what they say off the record! You can take this quote in many different ways but none of them are good. I am not going to say anything beyond the fact that I would be VERY suspicious if some sort of event occurred before the elections. Google the term “false flag.” Also remember Rahm Emmanuel’s famous quote of “you don’t ever want a crisis to go to waste; it’s an opportunity to do important things that you would otherwise avoid.” Think about this deeply. This doesn’t mean do what the public wants, or follow the constitution. It means that that those pulling the strings of power have the opportunity to do what THEY want, what fits THEIR ideology. Hitler is the most famous modern example of a leader that used a crisis to form his fascist state. Again, I am not talking about Obama in isolation. I am referring to the power structure that has been firmly in place since the 9/11 attacks. Many call it a silent coup. I agree with this assessment.

This email is not meant to create fear. It is actually meant to get people ready if things get crazy for whatever reason. It is a challenge to people. I challenge everyone to think about how they would react should another terrorist attack or something along those lines occur. I was there for 9/11 and I saw the buildings go down in person. I know what it was like to be manipulated by my own government and media in the wake of such an emotional trauma. I also see that what we have done since, with things such as the Patriot Act and two wars that are still ongoing, and I have reflected on how they have changed America for the worse and provided a fertile ground for the elite to take away more of our rights and our wealth. So my rallying cry is that we must be strong and fearless in the face of fearful events. In the wake of anything that may occur in the years ahead we must not react on emotion and NEVER give away our inalienable rights in the name of protection from big brother. Be fearless, strong and resolute. Spend more time with your neighbors and build things up at the local level. If we have those supports then we will be less inclined to cry to the magicians in D.C. and the Federal Reserve for “help.”

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Links, July 6

presenting the case for anti-cycylical fiscal policy; and fiscal retrenchment now would be pro-cyclical, making a weak economy with a huge output gap all the weaker

Are profits hurting capitalism? Yves Smith and Rob Parenteau, NYT.

picks up and expands on a point made in an article i linked to yesterday by Steve Waldman, re: capitalists not being capitalists enough.

Equities for the LOOOONNNNGGGG run. Jake, Econompic Data.

over the last 30 years, 10-yr strips have outperformed stocks

My Tea Party. James Howard Kunstler.

normally i would just link to this, but this post is well worth posting in full:

Now that congress has passed a fake financial reform bill that will accomplish absolutely nothing to correct a recently engrained culture of swindling, I want to start my own tea party. I don't want to associate it with the other tea parties that have already formed because I am allergic to much of the idiot ideology they express - especially the bent for merging Christian fundamentalism with governance.

One of the few things I agree on with the existing tea parties is that the Republicans and Democrats have made themselves hopeless hostages of political money and bargained away their legitimacy. In line with my general belief that American life must downscale or die, I'm not wholly persuaded that federalism can survive in any case - but assuming it will lumber on for a while anyway, the two major parties cannot retain their monopoly on power. Indeed, it is in the natural order of things that this country must periodically endure a realignment of political ideas and political power. This tends to occur during moments of cultural convulsion, and that is exactly the moment we are in as the sun sets on the fossil fuel based industrial extravaganza and we enter a crisis of intense resource austerity.

The other tea parties have been silent on the war because of the ties between Christian fundamentalism and military chauvinism. This is due, I suspect, to the tea parties first emanating out of Dixieland, where an old Scots-Irish "cracker" belligerence persists in a romantic view of violence - and where, coincidentally, there happen to be so many US military bases, and families dependent on careers connected with them. The confusions of hellfire Christian theology with governance form an overlayment on this, so you end up with a political culture favoring military adventures abroad and pushing citizens around at home on matters of social behavior (while mouthing a lot of disingenuous nonsense about "liberty").

I don't like that political culture and I'm not in favor of continuing our adventures on the fringes of the Middle East. The half-assed occupation of Afghanistan cannot be resolved in a way consistent with our fantasies and wishes. To put it as simply as possible, we can't control the terrain there and we can't control the behavior of the population. Our campaign to turn that remote and impoverished land into a governable democratic state is an exercise in futility that we can't afford. No doubt there are strategic wishes pinned to it - mainly a wish to influence and moderate neighboring Pakistan - but that appears to be back-firing with the minting of evermore Islamic maniacs seeking to blow up anything that presents a target, including their own women and children.

Iraq is a somewhat different story, but I suspect the bottom line is that we can't afford to run a police station there forever. In the worst-case of our leaving, Iran might attempt to step in and control the place (and its oil), but that would only produce a bloody collision of Arab and Persian culture - and the side effect of that might actually be to our benefit. Anyway, my tea party would shut down that operation ahead of schedule.

My tea party would reduce legal immigration to a tiny trickle and get serious about enforcing sanctions against people who are here without permission. A New York Times editorial last week expressed the Democratic-progressive view in typically tortured style, saying of the recent Arizona law:

..it makes a crime out of being a foreigner in the state without papers -- in most cases a civil violation of federal law. This is an invitation to racial profiling, an impediment to effective policing and a usurpation of federal authority....The fine distinction they want to apply in this matter between civil and criminal law is the same as NPR's house style of referring to illegal immigrants as "undocumented" - leaving the impression that the only problem for these people is a some bureaucratic glitch rather than a transgression of law. The truth is that neither party really wants to do anything about the extraordinary influx of Mexican nationals because they want to pander to a growing segment of Hispanic voters (or secondarily want to maintain the pool of cheap labor for US businesses). My party does not believe in unbounded multi-culturalism. My party also views the lawlessness of the current situation to be corrosive of the rule-of-law generally. My party views the global population overshoot problem as a condition that requires a more rigorous defense of US territory, sovereign resources, and even whatever remains of American common culture.

My tea party would systematically dismantle Too-Big-To-Fail banks into smaller units subject to real reforms that would prevent any further "socialization" of losses by financial buccaneers. In effect, my party would re-enact the Glass-Steagall laws - and get rid of the 3000-page bundle of prevaricating crap in the current "Fin-Reg" law, which has been constructed with all the guile and mendacity of a collateralized debt obligation. My party would seek the return of banking to its function as a

utility, while letting investment freebooters gamble with their own funds without any government back-up. (You'll see the investment houses get small fast that way.)My tea party would get the government out of the housing business. The main effect of 70 years of federal intervention for the sake of "affordable" housing has been to drive the price of housing up far beyond the ability of normal people to afford a place to live. And the current policies devised during the bubble crackup crisis have only served to prevent the price of houses from returning to a level where people might be willing to buy them. Of course, the whole process has also encouraged local governments to jack up property taxes to a level that can only be described as intolerable (in the 1776 sense of the word).

My party would undertake a rebuilding of the US passenger railroad system - not a flashy new "high speed" system, which we cannot afford, but the system that is lying out there rusting in the rain waiting to be fixed. This is imperative because we are on the verge of very disruptive problems with our oil supply which are going to put our beloved Happy Motoring matrix out-of-business. We also face the end of mass commercial aviation (even if flying remains an option for the wealthy). A restored passenger rail system will not solve all the problems connected with the demise of mass motoring, but it will help a lot, and would be an aid to the necessary re-activation of our small towns and cities as suburbia inevitably loses its value and utility.

The leaders of my tea party from the president on down would make a concerted effort to inform the public in straight talk about the real problems that we face involving peak oil and debt. My tea party would promote reality-based politics rather than techno-grandiose fantasies and wishful thinking. My tea party would encourage the necessary downscaling of all the critical activities of American daily life, including the re-localization of food production, the rebuilding of local commercial networks, the revitalization of the small towns and cities, and the difficult transition out of extreme car dependency. My tea party will do everything possible to construct a coherent consensus about what is happening to us and what we can do about it. My tea party is based on the true spirit of 1776 - the binding together of common interests and common culture - not the destruction of them as in the spirit of 1861.

late additions:

James Montier Resource Page. EuroShareLab.

Bond market worried about 1930s echo? Leo Kolivakis, Pension Pulse.

Will austerity be the catalyst for war? Dylan Grice, SocGen, via zerohedge.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Links, July 5

Why we're wired to make bad investment decisions. Michael Mauboussin, via Big Think.

The G-20's China bet. Simon Johnson, NYT.

Three market valuation indicators. Doug Short.

How Goldman Sachs gambled on starving the poor - and won. Huffington Post.

Time to shut down the Fed? Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Telegraph.

Rosenberg: sub-2% bond yields. Credit Writedowns.

Rob Parenteau gets sector balances right. Steve Waldman.

SW quoting RP:

"Remember the global savings glut you keep hearing about from Greenspan, Bernanke, Rajan, and other prominent neoliberals? Turns out it is a corporate savings glut. There is a glut of profits, and these profits are not being reinvested in tangible plant and equipment. Companies, ostensibly under the guise of maximizing shareholder value, would much rather pay their inside looters in management handsome bonuses, or pay out special dividends to their shareholders, or play casino games with all sorts of financial engineering thrown into obfuscate the nature of their financial speculation, than fulfill the traditional roles of capitalist, which is to use profits as both a signal to invest in expanding the productive capital stock, as well as a source of financing the widening and upgrading of productive plant and equipment.

What we have here, in other words, is a failure of capitalists to act as capitalists. Into the breach, fiscal policy must step unless we wish to court the types of debt deflation dynamics we were flirting with between September 2008 and March 2009. So rather than marching to Austeria, we need to kill two birds with one stone, and set fiscal policy more explicitly to the task of incentivizing the reinvestment of profits in tangible capital equipment."

Are we "IT" yet? Steve Keen.

a long paper with lots of charts --- and these notable excerpts, (as chosen by Yves Smith):

Firstly, the contribution to demand from rising private debt was far greater during the recent boom than during the Roaring Twenties—accounting for over 22% of aggregate demand versus a mere 8.7% in 1928. Secondly, the fall-off in debt-financed demand since the date of Peak Debt has been far sharper now than in the 1930s: in the 2 1/2 years since it began, we have gone from a positive 22% contribution to negative 20%; the comparable figure in 1931 (the equivalent date back then) was minus 12%.5 Thirdly, the rate of decline in debt-financed demand shows no signs of abating: deleveraging appears unlikely to stabilize any time soon.

Finally, the addition of government debt to the picture emphasizes the crucial role that fiscal policy has played in attenuating the decline in private sector demand (reducing the net impact of changing debt to minus 8%), and the speed with which the Government reacted to this crisis, compared to the 1930s. But even with the Government’s contribution, we are still on a similar trajectory to the Great Depression.

What we haven’t yet experienced—at least in a sustained manner—is deflation. That, combined with the enormous fiscal stimulus, may explain why unemployment has stabilized to some degree now despite sustained private sector deleveraging, whereas it rose consistently in the 1930s….

Whether this success can continue is now a moot point: the most recent inflation data suggests that the success of “the logic of the printing press” may be short-lived. The stubborn failure of the “V-shaped recovery” to display itself also reiterates the message of Figure 7: there has not been a sustained recovery in economic growth and unemployment since 1970 without an increase in private debt relative to GDP. For that unlikely revival to occur today, the economy would need to take a productive

turn for the better at a time that its debt burden is the greatest it has ever been..